Tears and Laughter: Women in Japanese Melodrama runs until Wednesday 29th November at the BFI Southbank. For more information and to book tickets, click here.

To read an interview with season curator and Sight and Sound features editor James Bell, click here.

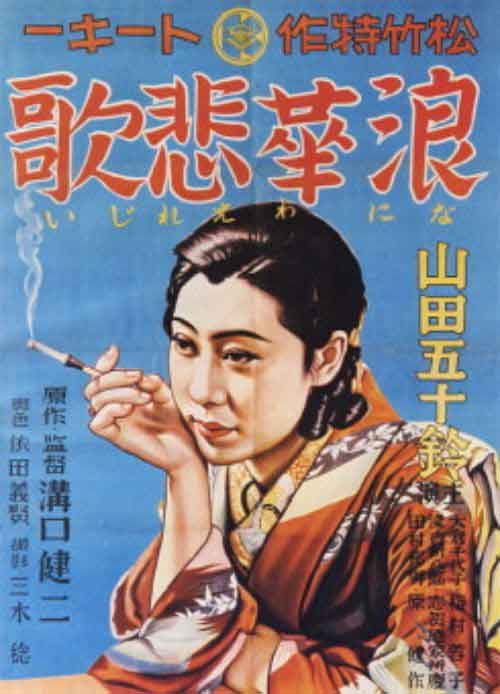

OSAKA ELEGY

Director: Kenji Mizoguchi

Writer: Yoshikata Yoda (screenplay), Tadashi Fujiwara (dialogue)

Cast: Isuzu Yamada, Yôko Umemura, Benkei Shiganoya

Cert: PG

Running time: 71mins

Year: 1936

What’s the story: To pay off her father’s debts and her brother’s university fees, young switchboard operator Ayako (Yamada) becomes her boss’ mistress. But, when he rejects her she is forced into prostitution.

What’s the verdict: A pre-war film from director Kenji Mizoguchi, the 1936 Osaka Elegy anticipates Japan’s rejection of Westernisation during the war years, plus the anger of the director’s post-war film Women of the Night.

Isuzu Yamada, the director’s pre-war muse, is the typical Mizoguchi heroine. Charismatic, resilient, and beset by misfortune, typically at the hands of men in authority. Toward the end of the film, when speaking to a local doctor about her situation, she labels herself a “female delinquent”. Her Western dress and defiantly cocked hat suggests a shift away from an image of demure Japanese femininity, and almost a challenge to the Imperial rule of the land.

As does a still-modern looking walk into camera as Ayako strides into an unknown future.

Mizoguchi employs his trademark long takes to record the action almost documentary style. An impressive crane shot following Ayako up the steps and along a balcony to her apartment is the kind of stylistic flourish expected in a Hitchcock thriller, and the central character’s predicament does generate tension.

Leavening this drama is a sharp line in farcical humour involving Ayako’s boss (Shiganoya) and his shrewd wife (Umemura). She’s aware of her husband’s peccadillos and demeans him in front of others for his weakness. In an alternate cinematic universe she and Ayako teamed up for a Yasuzo Masumura tale of female revenge on self-centered patriarchy.

WOMEN OF THE NIGHT

Writer: Yoshikata Yoda (screenplay), Eijirô Hisaita (novel)

Cast: Kinuyo Tanaka, Sanae Takasugi, Umeko Obayashi

Cert: 12 (TBC)

Running time: 75mins

Year: 1948

What’s the story: In post-World War II Osaka, Fusako (Tanaka) and her sister Natsuko (Takasugi), trying to survive despite numerous hardships, are pulled into a world of vice and violence.

What’s the verdict: In 1948, Mizoguchi had no time for leavening humour in this unflinching social conscience film born from the flames of the second war world.

Inspired by Italy’s street-level neo-realist movies such as Roberto Rossellini’s Rome, Open City made three years earlier, Women of the Night is made with an anger the director would later describe as barbarous.

A torn from the headlines hot topic story, it is far removed from his usual elegant style. In its rough n’ ready visuals (partly due to the available low-grade film stock) and down-the-barrel speechifying the movies sometimes feels like a public information film.

Mizoguchi employs his trademark camera crane tracking shots in a nightclub scene inside the pointedly named The Hollywood Club. Handsome technique sells a lifestyle of rare luxury out of reach to women unless they are prepared to sell their bodies, not just their labour.

At a brisk 75 minutes Mizoguchi and his regular scriptwriter Yoshitaka Yoda waste no time in placing both Fusako and Natsuko into the dirt of post-war Japan. Fusako loses her baby to tuberculosis and her husband is a casualty of war. In this economically volatile period, even secretary to a company director brings home only a meagre wage.

Shorn of sentiment but brimming with compassion, Women of the Night retains a power to shock. Syphilis and TB are everyday hazards, infant mortality commonplace. Fusako’s sister-in-law (Obayashi) is coerced into streetwalking and joins the older women on the bottom rung.

Yoda’s script pauses the drama for a male authority figure (policeman, doctor) to chastise the women for losing their purity and spreading disease amongst their countryfolk.

All this reaches an apotheosis of suffering when Fusako is beset by fellow streetwalkers. In the very Western confines of a ruined churchyard, she absorbs all society’s ills in an act of near martyrdom. It could slip into camp, but Tanaka’s fearless, ferocious performance makes this a stunning denouement.

After Women of the Night, Mizoguchi looked at the female experience in Japan’s past. Here he produced some of the country’s finest movies, including The Life of Oharu, Ugetsu Monogatari and Sansho the Bailiff. But, he would revisit similar story ground for his final film, Streets of Shame, starring Machiko Kyô.

CLOTHES OF DECEPTION

Writer: Kaneto Shindô

Cast: Machiko Kyô, Yasuko Fujita

Cert: PG (TBC)

Running time: 103mins

Year: 1951

What’s the story: In 1951 Gion, Kyoto’s geisha district, the hardnosed Kimicho (Kyô) works as a courtesan to support her mother’s ailing geisha house. Her sister Taeko (Fujita) is employed in a Tourist Office and yearns to run away to Tokyo with her beau.

What’s the verdict: Speaking of Machiko Kyô, she followed her sensational turn in 1950’s Rashomon with a complex performance in Kôzaburô Yoshimura’s Clothes of Deception.

Yoshimura directed dozens of movies, but is largely unknown in the West. Indeed, his writing partner Kaneto Shindô, with whom Yoshimura formed the production company Kindai Eiga Kyokai, is better known today, having directed such crossover successes as The Naked Island, Onibaba and Kuroneko.

Clothes of Deception was not a Kindai Eiga Kyokai production, made instead at Daiei Studio. A gripping melodrama and dark black comedy, it is also a modern-day reworking of Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1936 classic Sisters of Gion.

As a character says in the film Kyoto was spared Allied bombing raids during the war (due to the large number of sacred shrines located there the US forces knew would be important to win the subsequent peace). Consequently, the film is missing the visual starkness of Women of the Night and life seems less perilous six years after the surrender. Although tuberculosis remains an ever-present threat.

The geisha house operated by Kimicho’s mother is part of the community’s fabric and Kimicho herself is a local celebrity for her skills in “the trade”. Yet, as she is reminded by a rival geisha house owner, who has feuded with Kimicho’s mother over a past romantic conflict, they are not far from common prostitutes and men can be fickle in their affections. The women are selling a fantasy, but economic hardship and rejection are ever near.

Clothes of Deception (also known by the similarly apt title The Disguise, and the blunter moniker Under Silk Garments) depicts the tension between tradition and modernity that marks many a Japanese story. And was particularly relevant to the female experience in the post-war years.

Kimicho may seem the worldlier of the two sisters, but Taeko has the chance of escape, as signposted in her progressive career in a Tourist Office.

It is left to Taeko’s cousin, visiting Kyoto (the country’s old capital) from Tokyo (the new capital), to bemoan the antiquated culture still alive in the city. Boldly wondering if Kyoto being spared the bombing runs was entirely positive, she claims, “Beneath those old tiled roofs are lots of old tired ideas”. Potentially inflammatory, particularly coming from a woman in markedly Western dress, it’s a cutting slice of social commentary on a country still reeling from its war experience.

Despite a melodramatic ending involving a spurned knife-wielding suitor, Clothes of Deception remains sharp dark satire. Perhaps reflective of the time, it offers a cautiously optimistic ending absent from Osaka Elegy and Women of the Night.

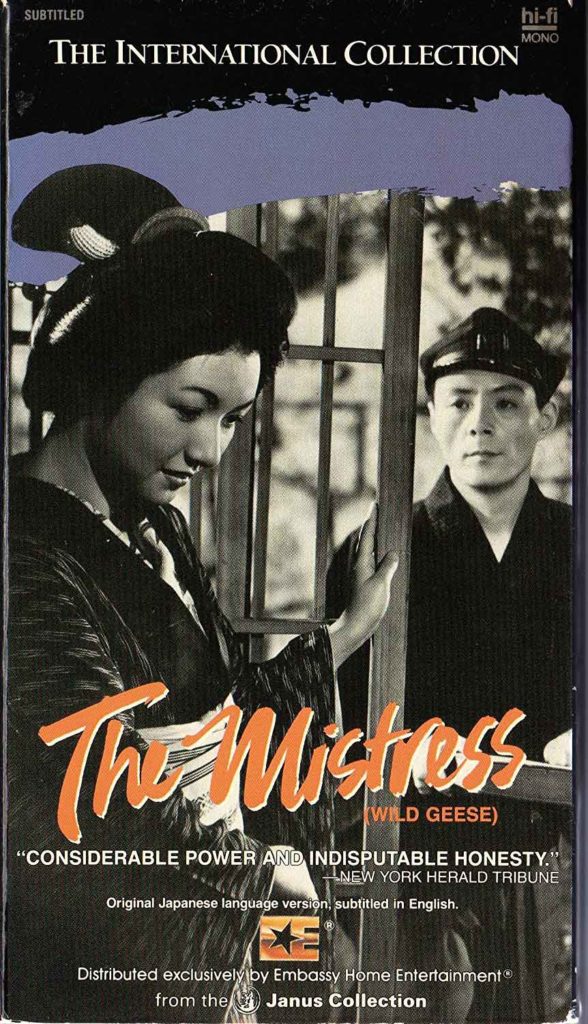

THE MISTRESS (aka Wild Geese)

Writer: Masashige Narusawa (screenplay), Ogai Mori (novella)

Cast: Hideko Takamine, Eijirô Tono, Hiroshi Akutagawa, Kumeko Urabe

Cert: PG (TBC)

Running time: 104mins

Year: 1953

What’s the story: In 1880s Tokyo, the beautiful Otama (Takamine) becomes the mistress of money lender Suezo (Tono). But, she falls in love with brilliant, sensitive student Okada (Akutagawa).

What’s the verdict: Adapted from Ogai Mori’s novella Gan (The Geese), The Mistress may be set in 1880s Tokyo of the Meiji era, but contained parallels with the post war situation in Japan.

The Meiji era marked the rapid expansion of Western influence and ideas throughout the country. Similar to the post-war period when the American occupiers promoted Western principles and suppressed such inherently Japanese concepts as bushido.

Heroine Otama’s profession of mistress also resonated in the post-war years, when the legality of geisha and prostitute as a profession were subjects of parliamentary debate.

Beyond social and historical interest, Toyoda’s The Mistress is heart-wrenching melodrama at its finest. Hideko Takamine, an actress best known for her collaborations with Mikio Naruse, is genuinely sublime as a woman cursed by beauty, pressured into supporting her ailing father through what amounts to prostitution.

Revealing turmoil through small gestures (abetted by well-placed stylistic flourishes), her climactic confession of disgust is show stopping. Takamine’s performance in the film’s dying moments sits intriguingly between despair and hope.

Toyoda and scriptwriter Narusawa resist easy moralising. Seuzo has risen from school caretaker to successful businessman, but his profession marks him an outcast. Meaning the community scorn Otama too, despite her spacious house and fine clothes.

Nominal hero Okada’s later behaviour appears cold to modern eyes, his rapid progression marking a fast-paced shift in society that will leave Otama behind. Plot time is made for Seuzo’s tormented wife Otsune (Urabe), allowed dignity beyond a shrew stereotype.

Finally, The Mistress is a beautiful example of Golden Age Japanese filmmaking. Impressive street sets and forced perspective matte paintings create a living, breathing Tokyo suburb, which blends wonderfully with period-dressed location photography.

As moving as Max Ophuls’ Letter from an Unknown Woman or James Ivory’s The Remains of the Day, The Mistress is a real discovery.

THE ETERNAL BREASTS

Writer: Sumie Tanaka

Cast: Yumeji Tsukioka, Ryoji Hayama

Cert: PG (TBC)

Running time: 106mins

Year: 1955

What’s the story: 1950s Sapporo, Northern Japan. Housewife and poet Fumiko Shimojô (Tsukioka) is enduring a failing marriage. At the moment her life seems to be starting anew, she is diagnosed with breast cancer.

What’s the verdict: An actress of legendary status in Japan, Kinuyo Tanaka was also the only woman to direct films during the country’s Golden Age. She helmed six movies from 1953 to 1962, of which The Eternal Breasts was her third.

Supported by important directors Yasujiro Ozu, Mikio Naruse and Keisuke Kinoshita (but curiously, not by Kenji Mizoguchi, with whom Tanaka made her most celebrated films), she also used her status to employ other women in key roles.

The Eternal Breasts was written by frequent Naruse collaborator Sumie Tanaka (no relation to the director) and the two women bring a pace and focus different to the male directed melodramas of the period.

The film is loosely based on the final few years of the life of poet Fumiko Nakajo, here Fumiko Shimojô. Although massaging her autobiography for the sake of efficiency (Nakajo had four children, Shimojô has two), this is a riveting study of an unusual Japanese woman.

Despite being devoted to her family, Shimojô is a prickly, layered character. After divorcing her faithless husband, she sloughs off social niceties. Refusing to attend her brother’s wedding as a divorced woman, she also pours scorn on the medium talent writers in her poetry circle who criticise the honesty in her work.

Post-mastectomy, her brush with death imbues Shimojô with a fresh lease of life, even as the cancer moves to other areas of her body. Exemplifying this is a newly awakened sexual desire, culminating in a genuinely tragi-erotic moment of happiness with sensitive reporter Ôtsuki (Hayama). Also notable is that Shimojô’s two children are absent for a large portion of the film’s latter half, the story focussing on the brief blossoming of the woman herself.

Tanaka shoots the opening part of the film as Gothic melodrama, heavy shadows literally looming over the characters within Shimojô s cold marital home. Boldly, post-op The Eternal Breasts brightens up, despite the impending tragedy.

Shadows return in the final stages of the film, particularly in a disturbing sequence when Shimojô visits the morgue gates one foggy night and sees the route of her final journey.

After appearing in Tanaka’s 1953 directorial debut Love Letter, Tsukioka here graduates to lead role. Her Shimojô is sensitive and spirited, broken and resilient, in essence, defiantly human.

AN INLET OF MUDDY WATER

Writer: Yôko Mizuki, Toshirô Ide (screenplay), Ichiyo Higuchi (based on stories by)

Cast: Yatusko Tan’ami, Yoshiko Kuga, Chikage Awashima, Haruko Sugimura

Cert: PG (TBC)

Running time: 130mins

Year: 1953

What’s the story: Three different stories depict the hardships of women in Meiji era Japan.

What’s the verdict: Little known in the West, in 1953 Tadashi Imai’s An Inlet of Muddy Water placed no.1 on the Top 10 of the Year list by Kinema Junpo magazine (Japan’s equivalent to Sight and Sound). At number 2 was Tokyo Story, giving some indication of how highly An Inlet of Muddy Water was regarded.

Whether it bests Ozu’s masterpiece would make an interesting debate. But, over 60 years later, An Inlet of Muddy Water remains a dazzling mix of social drama and psychological thriller.

A portmanteau film, across three stories the trials of multiple women on society’s fringes unfold. The Thirteenth Night features Tan’ami as Seki, a working-class girl trapped in a cruel marriage with an upper class businessman. Comprising two lengthy conversations, with her parents and someone from her past, it’s a powerful opener, brimming with pathos, regret and grim stoicism.

On the Last Day of the Year features Kuga as O-Mine, servant to a shrewish lady. The lady is maneuvering for her daughters to inherit her husband’s fortune, but her wastrel stepson is first in line. When O-Mine cannot secure a loan from her boss to help her poor aunt and uncle, she does something rash and fearfully awaits the consequences. Lightest of the three stories, the middle segment has a wryly optimistic punchline and is anchored by Kuga’s emotive performance.

Toward the end of On the Last Day of the Year, Imai introduces expressionistic lighting and camerawork to convey O-Mine’s fretful state. Stylistically, this leads into the third story, lengthiest of the three and named after the film’s title.

In An Inlet of Muddy Water, Awashima is Oriki, number one girl at a brothel in Tokyo’s Yoshiwara red light district. Tormented by her profession, she is nonetheless despised by Sugimura’s Ohatsu, wife of a man (Miyaguchi) who squandered their money on Oriki and put them on skid row.

Deeply affecting and dynamically shot, An Inlet of Muddy Water deftly weaves together the lives of two different women who risk losing everything due to destructive male desire. Tight, wide angle shots literally bring the brothel and its clientele looming over Oriki as her job overwhelms her.

Dynamic use of low angle deep focus, similar to Orson Welles or Imai’s contemporary Kenji Mizoguchi, allows the eye to move between the different women working in the brothel during well-staged group scenes.

A key flashback sequence is presented entirely without dialogue, Imai using physical performance and expressionistic visuals to reveal one character’s unhappy childhood. A drunken orgy, in which an older prostitute who was once the prized catch is thrown out into the garden, is genuinely troubling.

The conclusion is predictably downbeat, with a coda that bitterly shows this was all just another day in Yoshiwara.

Underseen in the West, by a director ripe for rediscovery, this is a superlative example of Japanese melodrama.

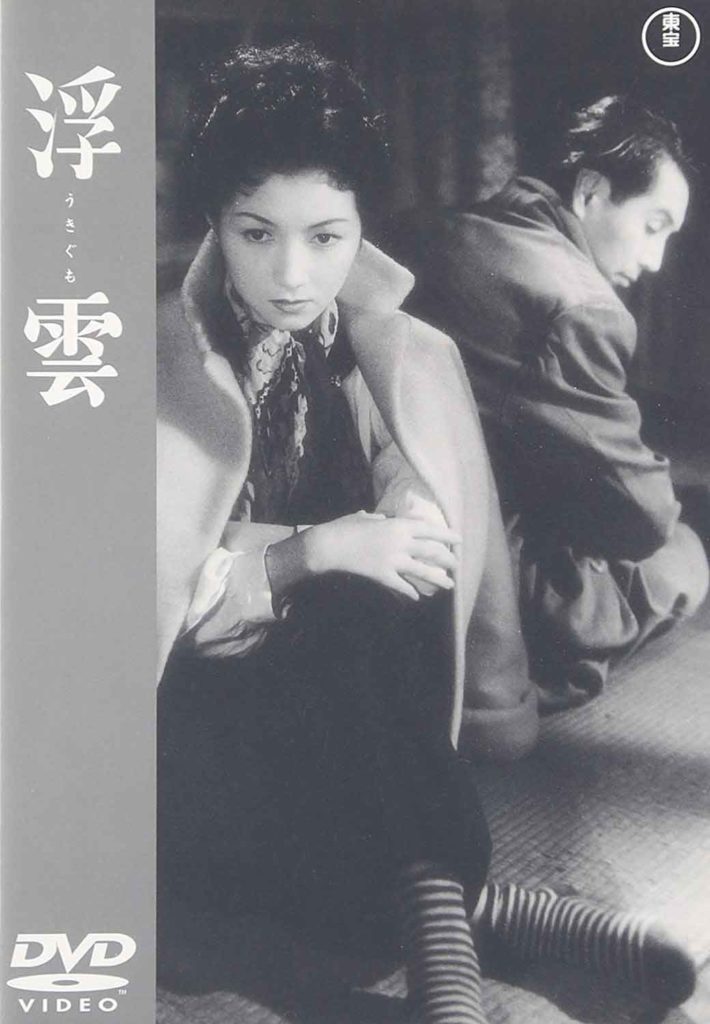

FLOATING CLOUDS

Writer: Yôko Mizuki (screenplay), Fumiko Hayashi (novel)

Cast: Hideko Takamine, Masayuki Mori, Mariko Okada, Isao Yamagata, Roy James

Cert: 12

Running time: 123mins

Year: 1955

What’s the story: In post-war Tokyo, Yukiko (Takamine) and Tomioka (Mori) are trapped in a love/hate relationship following a wartime affair.

What’s the verdict: In Kinema Junpo’s most recent Top 10 Japanese Films of All Time, Mikio Naruse’s Floating Clouds placed no.3, behind Tokyo Story and Seven Samurai in first and second position.

Unsurprising, as this study of a destructive relationship in the ruins of 1946 Tokyo is a fascinating examination of the country’s postwar mindset. Ex-Forestry employees Yukiko and Tomioka, based in Vietnam during the war on a research project, repeatedly split up and circle each other, professing love and him serially cheating and her spitting invectives.

This doomed love affair could be read as the national mood after the war when the country was shattered by its defeat. And in Yukiko’s emotional masochism is there a kind of tacit acknowledgement of postwar guilt?

Naruse was working from Fumiko Hayashi’s source novel, his fifth adaptation of the author’s works, so was in familiar territory. He and frequent collaborator Mizuki created a story more overtly melodramatic than usual for the director, but never tip the tale into hysterics.

Confidently structured, large ellipses are revealed to be contained in simple cuts between scenes, intrigue generated as fortune is revealed to either be smiling upon or smiting Yukiko or Tomioka.

Plausibly migrating from wounded lover to caustic survivalist, Takamine proves herself one of Japan’s finest actresses. Yukiko’s devotion to Tomioka could have been gigglesome with a lesser talent, but she conveys depths of conflicting emotions through a small gasp or bitter smile.

Naruse is not afraid to introduce dark subject matter (rape, suicide, abortion) and once more it is testament to Takamine that her character is not swamped by hardship.

Floating Clouds also features background details of postwar Japan – Yukiko briefly dates an American G.I. (James), her loathsome brother-in-law (Yamagata) begins a scam cult to fleece anxious city folk.

Mariko Okada, who would later make a series of anti-melodramas with husband Yoshishige Yoshida, also impresses in a key supporting role as a callow young woman who catches Tomioka’s roving eye.

Frequent, expressionistic, rainfall swells to a typhoon in the climactic moments when nature itself seems to rage against the injustice suffered by Takamine’s heroine. Breathtaking.

THE SHAPE OF NIGHT

THE SHAPE OF NIGHT

Director: Noboru Nakamura

Writer: Toshihide Gondo (screenplay), Kyoko Ota (novel)

Cast: Miyuki Kuwano, Mikijiro Hira, Keisuke Sonoi

Cert: 18 (TBC)

Running time: 109mins

Year: 1964

What’s the story: Young prostitute Yoshie (Kuwano) must choose between her yakuza pimp boyfriend Eiji (Hira) and customer Fujii (Sonoi), who offers an escape route from her life.

What’s the verdict: He is largely unknown in the West, yet based on The Shape of Night director Noboru Nakamura’s filmography promises many rewards.

Visually striking, The Shape of Night tells the disturbing tale of young factory worker Yoshie, who part-times at a local bar where she falls for the suave Eiji. But, her new beau is a low-level hood who is soon pimping her out to pay his tribute to a vicious crime boss.

Told largely in flashback, via encounters with conflicted john Fujii, who wishes to rescue Yoshie, Nakamura’s film is a real discovery. The elegance of Wong Kar-wai meets the social rawness of Shohei Imamura for an experience not soon forgotten.

Kuwano delivers three distinct performances: ice-cool escort, tormented slave of her oily pimp, and fresh-faced livewire in early flashbacks.

Nakamura’s compositions and bold use of colour transfix the eye, even as Yoshie endures ordeals that would make Lars von Trier recoil. In a case of less is more, the director focusses his camera on the actress’ face during extreme moments. Or Eiji’s in one scene that continues to disturb more than 50-years after release.

Elevating this above exploitation pulp is direction inspired by the French New Wave (brief shots of neon signs are short-hand for Yoshie’s gaudy, emotionless encounters with clients), plus a fascinating power struggle between the abused woman and her pimp boyfriend.

Kuwano was prolific in movies for 12 years, starring in such films as Kurosawa’s Red Beard and Oshima’s Naked Youth, before retiring in 1967. Her work here is an impressive record of her talent.

Rob Daniel

Twitter: rob_a_Daniel

iTunes Podcast: The Electric Shadows Podcast

Pingback: Kristy Matheson on Kinuyo Tanaka: A Life in Film

Pingback: Tokyo Story - Yasujiro Ozu's masterpiece astounds almost 70 years later