Writer: John Clifford

Cast: Candace Hilligoss, Sidney Berger, Frances Feist, Art Ellison

Cert: 12

Running time: 78mins

Year: 1962

Film:

Extras:

What’s the story: Young organist Mary is the only survivor when her friend’s car crashes off a bridge into a river. As she attempts to start a new life in a different town, a frightening stranger begins to stalk her.

What’s the verdict: British film fans skirting around the age of 40 are likely to have first encountered Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls courtesy of Alex Cox. Cox screened it in the summer of 1991 as part of his essential Moviedrome series (and his intro can be seen here).

Those of us who saw it that Sunday night were still reeling from the recently released The Silence of the Lambs. Now here was another modestly budgeted horror movie (very modest in the case of CoS) with an unusual, chilling atmosphere and well-timed shocks.

Carnival of Souls was the brain child of Kansas based corporate film director Harvey (not a Chevy dealer as Cox supposes in his intro). Driving through Utah one evening, Harvey happened across the huge, outlandish Russian-themed pavilion Saltair, built beside that state’s Great Lake. Struck by its uncanny vibe, Harvey imagined Saltair’s vast ballroom playing host to a dance of the dead, and charged his regular writing partner John Clifford with penning a script that featured both the strange location and that sequence.

What Harvey and Clifford produced, on the miniscule budget of $30,000, is one of horror cinema’s best examples of the uncanny. Are the movie’s strange events and ghoulish figures symptoms of Mary’s PTSD? Or are stranger agencies at play?

To modern eyes the answer is guessable. As it was apparently to audiences in 1989, when the film received a festival circuit re-release and critical appreciation grew. 1962 audiences were not as savvy to radical plot shifts, although the story does echo a 1960 episode of The Twilight Zone we’ll not name here for risk of spoilers.

But, there is more to Carnival of Souls than its climactic reveal. Clifford’s layered, literate script is peopled with characters and dialogue that raise the film above what Herschell Gordon Lewis would do with indie horror cinema a year later in Blood Feast.

For an early 1960s chiller, Hilligoss’ Mary Henry is a fascinating female lead. Tremulous in the pre-credit drag race that causes the crash, after emerging from the river she is born again a tougher figure. Aloof and pragmatic, she leaves town after the accident (in a driving sequence through open desert reminiscent of 1960’s Psycho) to become a church organist in nearby Utah. Not for spiritual reasons, as she informs letchy neighbour Linden (Berger), “To me a church is just a place of business”.

Hilligoss’ performance is pitched perfectly between staunch rationalism and terrified confusion when reality begins to slide, the actress carrying almost every scene of the film.

Clifford’s script subtly circles that opening crash with later events. Mary’s landlady (Feist) repeatedly reminds her tenant she can take as many baths as she wants. Male threat looms throughout. Boy racers are responsible for Mary’s friend’s car crashing off the bridge. To modern eyes Linden is a sex pest. A minister (Ellison) fires Mary when delirium causes her to play wild music on the church organ.

And, most threatening of all are sudden appearances by the ghoulish figure credited as “The Man” (director Harvey, resembling a ghoulish mortician), who seems to be a kind of emissary.

Harvey’s direction is as subtly disquieting as his writer’s screenplay. Shot and edited with the brisk efficiency of a Twilight Zone episode (3 weeks for filming, 3 weeks in the edit suite), Harvey captures that show’s ability to capture the everyday and then take one step outside reality.

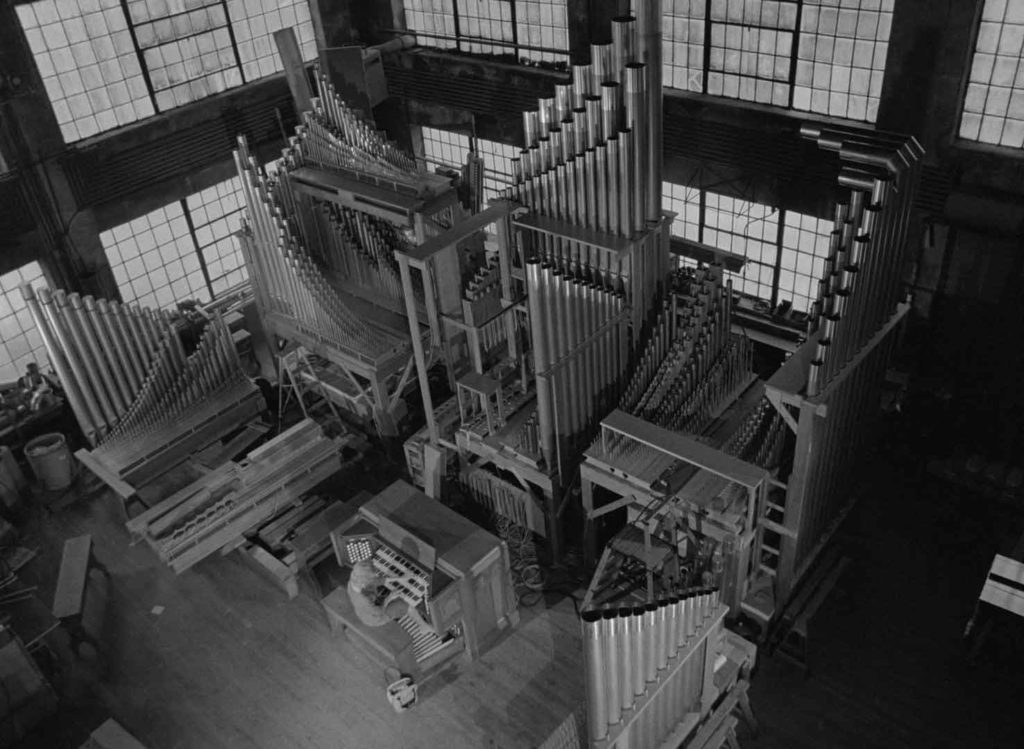

Foreshadowing the vast Saltair pavilion and its secrets are earlier scenes in a huge organ factory, shot from a dizzying height, and the cavernous church in which Mary finds employment.

Men are repeatedly framed from behind as if the visuals are masking their true intentions. The ghoulish figures haunting Mary appear from disorienting angles or spaces, often moving at unusual speed.

On two occasions the world shifts into a space without sound save Mary’s own voice and footsteps as she seems to vanish despite still being present.

Gene Moore’s score, performed exclusively on church organ, deftly weaves in and out of Mary’s own playing and sets nerves on edge.

Even technical limitations enhance the atmosphere. Badly synched dialogue in the scene after the crash suggest we’re not in Kansas anymore (although at that point the players literally were).

Despite finding little success upon initial release, TV showings of Carnival of Souls influenced later filmmakers. The film’s visual style and the ghouls’ appearance can be felt in George A. Romero’s 1968 game-changer Night of the Living Dead.

David Lynch seems particularly struck by Harvey’s film. Eraserhead contains its DNA, Twin Peaks and Mulholland Drive are similarly puzzle box in structure and ape the off-kilter performance style, and Lost Highway’s Mystery Man is a spiritual descendant of The Man.

If you’ve yet to join the danse macabre get into the rhythm now…

DISC AND EXTRAS

The Criterion Collection’s 2K restoration is astonishingly crisp and clean. The company elected against carrying over the Director’s Cut from their original DVD release due to the extra scenes being sourced from one-inch video (although some sections of it are included as deleted scenes).

Herk Harvey and John Clifford’s scene-specific commentary, taken from a 1989 interview, brims with production information and goals. Including their lofty mission statement that the film has “the look of Bergman and the feel of Cocteau”.

Background information on the cast includes the fact that Hilligoss studied at Lee Strasberg’s Actors Studio alongside Marilyn Monroe and Roy Scheider.

Final Destination, a 23-minute interview with The Simpsons writer and producer Dana Gould, is an engaging appreciation of the movie.

David Cairns’ 23-minute video essay is an inventive review of the film, featuring input from film commentators Anne Billson and Fiona Watson.

The Movie That Wouldn’t Die is a local news documentary made in Topeka, Kansas for the 1989 re-release about the film’s lasting legacy. Particularly welcome are excerpts of the cast and crew press conference, including Harvey in full make-up as The Man.

The Carnival Tour is a 1999 5-minute short from the same news team, on Carnival of Souls’ locations then and now.

A 32-minute documentary on Saltair is visually low-grade, which adds to the creepy appearance of the pleasure pavilion and its bizarre history. It burnt down repeatedly, was made redundant when the Salt Lake receded by half a mile, and then in the early 1980s was submerged when the water level rose once more!

Want more? 27-minutes of Outtakes, silent and set to Gene Moore’s score, show production filming around Lawrence, Kansas and Saltair.

Over an hour of industrial and educational shorts Harvey and Clifford produced for the Centron Corporation reveal Carnival of Souls’ unreal atmosphere sometimes cropped up in their day jobs.

A trailer and accompanying booklet complete an excellent presentation of an unusual, chipped gem.

Rob Daniel

Twitter: rob_a_Daniel

iTunes Podcast: The Electric Shadows Podcast

[su_youtube url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YQfOJ4ZKP3Y”]