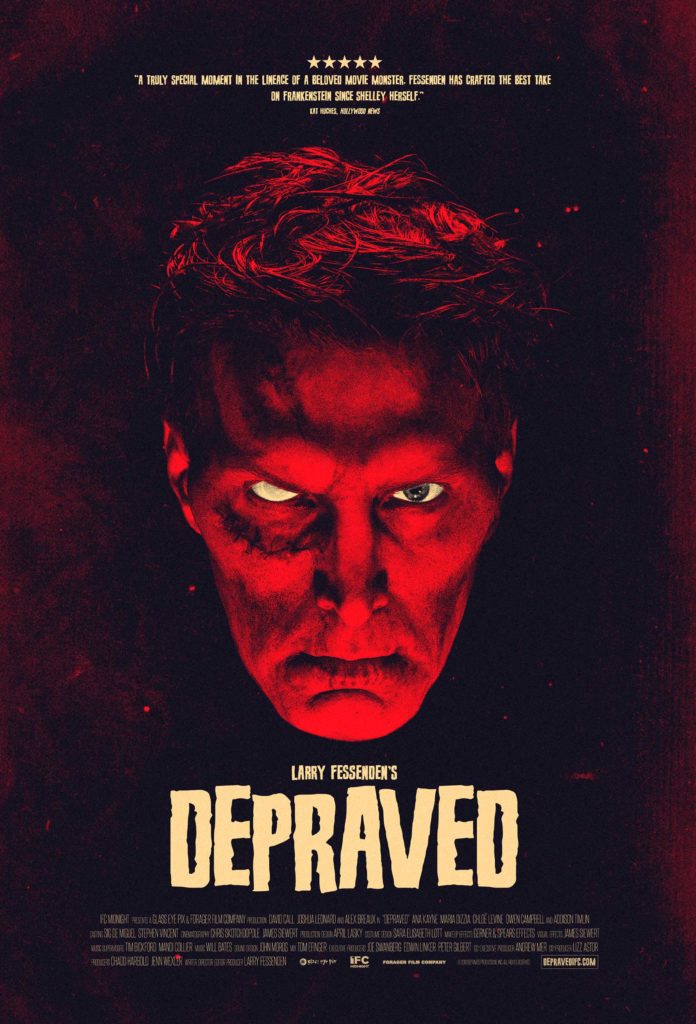

Director: Larry Fessenden

Writers: Larry Fessenden

Cast: David Call, Alex Breaux, Owen Campbell, Joshua Leonard

Producers: Larry Fessenden, Chadd Harbold, Jenn Wexler

Music: Will Bates

Cinematography: James Siewert, Chris Skotchdopole

Editor: Larry Fessenden

Cert: 18 (TBC)

Running time: 114mins

Year: 2019

What’s the story: In Brooklyn, a traumatised military surgeon constructs a person out of separate body parts.

What’s the verdict: Two centuries after its subject first took life in our collective imagination, artists are still drawing inspiration from the now-archetypal story of Frankenstein and his monster.

The universal scope of its themes – good vs. evil, man vs. nature – rarely lend themselves to intimacy; last year’s Frankenstein’s Creature being a rare exception. Adaptations typically aim for the grand opera of the thunderstorm that brings the creature to life, itself an invention of cinema; a literalisation of the elusive “spark of life”.

In Depraved, writer-director-producer-editor-hyphenate Larry Fessenden instead uses the limitations of budget and location imposed by indie filmmaking to experimental effect.

The film takes the radical step of giving us a glimpse of the man before he becomes The Monster: earnest, floppy-haired millennial Alex (Campbell), who, walking back from his girlfriend’s flat, is abruptly stabbed and killed by an unknown assailant.

His resurrection is accompanied by visions of lightning, witchy woods and anatomical sketches. By the time he awakens on the slab, Alex has become Adam (Breaux), the blank-slate science project of former army medic Henry (Call). However, rather than running off and abandoning his creation, as the text would have it, Henry sets about rehabilitating him.

Fessenden presents these scenes largely from Adam’s perspective; staying on his face, slack and gaunt as, during their first encounter, Henry’s voice fades into an indistinguishability. Phosphenes, light phenomena, intermittently play across the screen – multiplying balls of viral green, laser-pointer-fireflies of red, a kaleidoscope of fractured blue energy like a game of Asteroids.

Breaux perfectly captures Adam’s dawning comprehension, as shape sorting progresses to puzzle boxes; his hair growing back, the scars fading, that misty blue eye coming into focus.

We also become acquainted with Henry: caring but callow, easily frustrated; not a natural father figure. If Henry is an imperfect God, his benefactor, Polidori (Leonard, The Blair Witch Project), is a Satan of sorts.

An original character – presumably named after the writer of The Vampyre, a product of the same literary contest that produced Frankenstein – Polidori is a louche, wealthy pharmaceutical rep, supplier of the regimen of little red pills Henry reluctantly provides Adam as part of an off-the-books drug trial.

While Henry prefers to keep his creation tucked up in bed, in a patchwork quilt no less, Polidori wants Adam to experience the finer things in life. The Museum of Modern Art… strippers and cocaine.

Fessenden carefully stitches these disparate elements into the loose framework of Mary Shelley’s narrative, grafting severed nerve endings to contemporary issues as specific as society’s failure to treat PTSD.

In doing so, he sets about reintegrating the Postmodern Prometheus. Flashbacks hint at Henry’s trauma from Afghanistan, what might compel a man to such desperate ends. Conceptually, it’s compelling; emotionally, it’s somewhat remote – not quite, if you’ll pardon the cliché, the sum of its parts.

Depraved is ultimately swept along by Shelley’s narrative, going full-tilt Gothic in a way that feels at odds with what’s come before. The notion of depravity espoused by Polidori, that mankind is inherently a corrupt destroyer, doesn’t feel entirely earned. Nor does the film entirely support it, but does not carry the ambivalence to challenge it. Characters may be flawed, myopic, self-interested, but they’re too lightly sketched for us to attach much weight to their philosophies.

A transition from the still-intact ear of Van Gogh in self-portrait to the scarred ear of Adam is provocative, but not when left abstracted from any real context.

That Fessenden edits, too, is credit to his auteur credentials, as well as producing the film through his company Glass Eye Pix.

James Siewert and Chris Skotchdopole’s cinematography is stark, grainy – “real”. Will Bates’ score supports the feeling of authenticity, blending gentle electronica with ambient noise, as does the New York industrial estate (Gowanus in Brooklyn to be precise) in which the film is largely set.

If only it had some heart to go along with the brains.

Rob Wallis

Twitter:@robertmwallis

Website:www.ofallthefilmsites.com

Podcast: The Electric Shadows Podcast