Director: Jennifer Kent

Writer: Jennifer Kent

Cast: Aisling Franciosi, Sam Claflin, Baykali Ganambarr, Damon Herriman, Michael Sheasby

Producers: Kristina Ceyton, Bruna Papandrea, Steve Hutensky, Jennifer Kent

Music: Jed Kurzel

Cinematography: Radek Ladczuk

Editor: Simon Njoo

Cert: 18

Running time: 136mins

Year: 2018

What’s the story: 1825, Tasmania. Following a terrible assault on her and her family by British soldiers, Irish ex-convict Clare (Franciosi) pursues them through harsh wilderness to exact revenge.

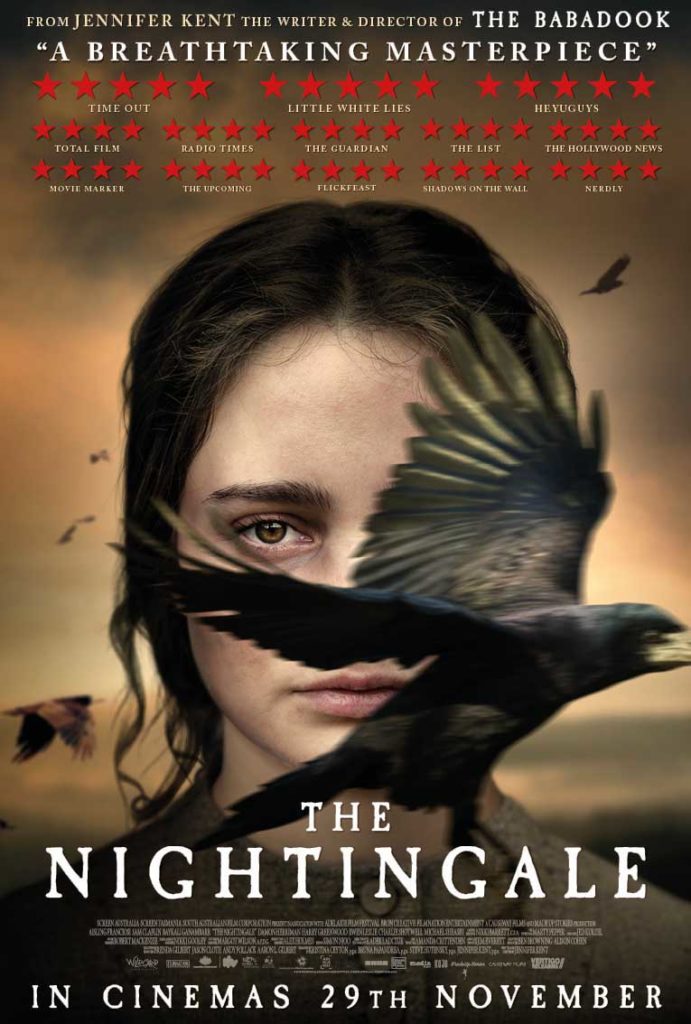

What’s the verdict: After scoring a bullseye with debut feature The Babadook, Jennifer Kent returns with the ferocious, and ferociously intelligent, The Nightingale.

The basic plot echoes grindhouse rape-revenge movies. But, from the savagery Kent conjures a remarkable story of resilience and ultimately compassion in the face of violence and hatred.

While not easy viewing, that “18” certificate is warranted, those who tough out the opening fifteen minutes will be rewarded with one of the year’s best movies.

Set in the wilderness of 19th century Van Diemen’s Land (now known as Tasmania), the film centres on Clare, an Irish ex-convict denied papers of freedom by the brutal Lieutenant Hawkins (Claflin). When Clare’s husband, Aidan (Sheasby), confronts Hawkins for keeping his wife enslaved, the military man retaliates with appalling violence.

Hawkins, accompanied by a small troop, subsequently journeys north to seek a captaincy. With the British authorities refusing to help, Clare ventures into the wilderness in pursuit. Reluctantly joining her is Aboriginal tracker Billy (Ganambarr), who too has suffered terrible losses at the colonisers’ hands.

Fittingly, The Nightingale echoes the Greek myth of Philomela and Procne, about a princess transforming into a nightingale after exacting revenge on the man who raped her. Kent’s film has the feel of an epic fable refracted through a feminist lens, set in a lost paradise beset with aggressors branded “white devils” by indigenous tribes.

Dodging sensationalism, the writer-director depicts the corrupting effects of violence. How it kicks down through classes and military ranks, brutalising young and old, destroying people and cultures. It’s in the misogynistic dialogue the soldiers use to belittle subordinates. In the commonplace assaults on female convicts and tribeswomen and the nightmares that plague Clare. And in how the near genocidal fury of the colonisers, fighting what was dubbed “The Black War”, leaves Aboriginal bodies strewn across the land.

Yet, rather than embarking on a Kill Bill style rip-roaring rampage of revenge, Kent explores the corrosive effects of violence and ways out of it. A climactic dialogue confrontation is as dramatic as the preceding bloodletting and the closing moments dare to offer a sliver of hope.

Shot with shallow lenses in the square Academy ratio, even in the vast Tasmanian forest and mountains The Nightingale is tense and claustrophobic. After Monos, this is the second 2019 film to showcase why shooting on location offers a more vivid experience than filming against greenscreen.

Franciosi carries the film with an astonishing performance of anger and humanity. A riot of emotions creases her face, often one on top of another, the weight of her mission exacting its own revenge.

First-time actor Ganambarr is perfect as Clare’s guide, his Billy mirroring his companion in trauma and empathy. The film also twins them through birds: Clare is dubbed nightingale for her singing voice, while Billy’s spirit animal is the blackbird. Both suggest some future freedom from the world holding them.

Avoiding one-note villainy, Claflin’s Hawkins is an all-too human villain. Driven by ambition and entitlement, his deceptively soft manner gives way to horrendous, accountability free, cruelty.

Damon Herriman’s callous and craven Sergeant Ruse is a study in class subservience, as dazzling as his Charles Manson in Netflix’s Mindhunters was a portrayal of charismatic madness. Coincidentally, Herriman plays that eternal bully-boy Mr. Punch in Mirrah Foulkes’ similarly themed Judy and Punch.

Disturbing but exhilarating, The Nightingale joins The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, Rabbit Proof Fence and The Proposition as a moving, powerful meditation on Australia’s past.

Rob Daniel

Twitter: rob_a_Daniel

iTunes Podcast: The Electric Shadows Podcast